We know our voice when we see it. Hand a writer ten unmarked paragraphs, one of them their own. They'll spot it at once. But ask them to describe that voice? "It's.. casual but smart? Kind of chatty with some edge?" These vague labels work fine for human readers. They're useless for AI, which needs concrete patterns to copy.

This gap between feeling and stating is the core problem of AI-assisted writing. We can feel our voice. But we can't spell it out. The result is prose that sounds like everyone and no one. It's competent but lacks the mark that makes writing ours.

The fix comes from a surprise source: stylometry, the data-driven study of writing style. What feels impossible to pin down about voice turns out to be quite measurable. And once we can measure it, we can teach it to AI.

The Five Dimensions of Measurable Style

Scholars who analyze writing style have found patterns that tell one writer from another.[1][2] We can group these into five areas that matter most for writers using AI. Each offers concrete metrics we can note down and share.

1. Sentence Architecture

Every writer has a structural mark. Some favor short, punchy claims. Others build long, layered sentences with clauses that unfold like origami.

What to measure:

- Average sentence length (words per sentence)

- Variation in sentence length (mixing short and long, or staying consistent?)

- Complexity: simple sentences vs. compound vs. complex with clauses

- Fragment usage (deliberate incomplete sentences for emphasis)

Why it matters to AI

Large language models make sentences with less length variety than humans. They produce uniform structures that smooth over our natural rhythm. Whether we write in punchy 12-word bursts or flowing 35-word runs, AI flattens that variety unless we give it clear structure rules.

2. Lexical Fingerprints

The words we reach for, again and again, form a word signature as unique as our handwriting.

What to measure:

- Contraction frequency (we're vs. we are, it's vs. it is)

- Favorite intensifiers (very, really, absolutely, quite, fairly)

- Conjunction preferences (but vs. however, and vs. also, so vs. so)

- Vocabulary level (common words vs. specialized or unusual choices)

- Signature phrases (the verbal tics that friends would recognize)

Why it matters to AI

AI defaults to formal, neutral words. If we write "folks" instead of "people," or use "actually" as a verbal shrug, those patterns won't show up in AI output on their own.

3. Rhythm and Pacing

Writing moves through time. Some writers sprint in short chunks. Others take readers on long, slow strolls. Punctuation creates rhythm as unique as a musical style.

What to measure:

- Paragraph length (single-sentence emphasis paragraphs vs. large blocks)

- Punctuation patterns (em-dash frequency, semicolon usage, parenthetical asides)

- White space deployment (frequent breaks vs. dense blocks)

- List usage (how often, and in what style)

Why it matters to AI

Without clear guidance, AI makes uniform paragraphs that don't reflect our natural variety. If we use one-sentence paragraphs for punch, or long flowing ones to build mood, or heavy em-dash use for asides, we must state this clearly.

4. Rhetorical Moves

Every writer builds habitual ways of entering and leaving ideas. We all have patterns for making arguments and linking thoughts.

What to measure:

- Opening patterns (Starting with questions? Assertions? Anecdotes? Data?)

- Transition style (Explicit connectives like "Also" vs. implicit logical flow)

- Evidence deployment (Claim-first then support, or build evidence then conclude?)

- Closing patterns (Summary? Call to action? Provocative question? Circular return?)

Why it matters to AI

Without clear templates, AI gives generic "intro-body-end" form. Our own approach, like opening with a scene, using questions as section breaks, or ending by looping back to our opening image, needs stated rules.

5. Perspective and Stance

Our bond with ideas and readers creates a distinct mental posture.

What to measure:

- First-person frequency (I, we, my, our: how often do we appear in our prose?)

- Direct fix (How directly do we speak to readers?)

- Hedging patterns (might, seems, could, perhaps vs. is, will, does, clearly)

- Certainty markers (Are we confident or tentative? Direct or qualified?)

Why it matters to AI

Without clear rules, AI leans toward third-person and hedging that may not match us. If we write with strong "I" presence and bold claims, or prefer "we" with careful caveats, that stance needs to be spelled out.

What Stylometric Diversity Actually Looks Like

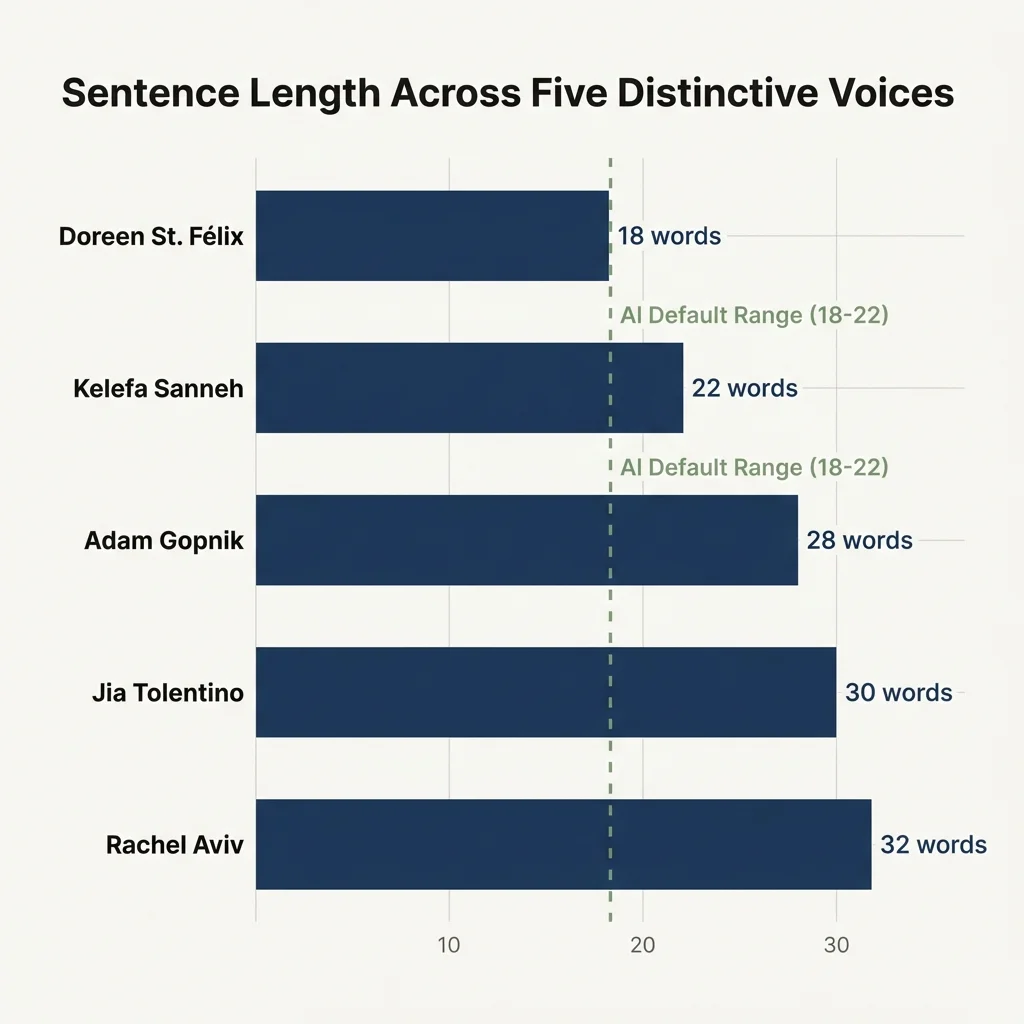

To see how these traits vary across real writers, we can look at samples from five New Yorker voices: Jia Tolentino, Rachel Aviv, Kelefa Sanneh, Adam Gopnik, and Doreen St. Félix. Each brings a clear voice to the page. Yet the patterns under that voice differ sharply.

Sentence Architecture

Rachel Aviv's long-form pieces feature sentences that often exceed 40 words. They build nested structures that mirror the complex minds of her subjects. One of her sentences on Oliver Sacks runs to 67 words without losing clarity. Doreen St. Félix, covering celebrity and culture, favors shorter forms. Many of her sentences are under 20 words. This creates a rhythm that matches the fast media world she critiques.

Lexical Signatures

Jia Tolentino reaches for philosophical and sociological words ("structural violence," "context collapse") even when writing about Sephora tweens or CEOs. Her contractions are moderate. Her intensifiers are understated. Adam Gopnik favors elegant Latinate words ("ramrod patrician," "diaphanous") while keeping a chatty tone through personal stories. His prose feels both complex and warm at once, a hard balance.

Rhythm and Punctuation

Tolentino uses em-dashes heavily, sometimes three or four per paragraph. This creates a rhythm of cut-off thoughts and sudden asides. Gopnik favors long flowing sentences with semicolons and colons that unfold ideas step by step. Sanneh uses parentheticals on purpose. He drops in context or caveats without breaking his main argument's flow.

Rhetorical Structure

Aviv builds slowly. She often spends 500+ words setting a scene before her central question appears. St. Félix opens more boldly, stating her critical frame early. Gopnik weaves between personal memory and cultural analysis. He uses his own life as evidence. Sanneh tends toward an observer's stance: third-person with brief first-person drops.

Perspective Patterns

Tolentino writes in heavy first-person. She often puts herself inside the patterns she critiques. Aviv keeps third-person even when dealing with deep emotional topics. Gopnik uses "I" freely but pivots fast to broad claims. St. Félix stays mostly in critical third-person, with a "we" here and there to mark shared ground.

The range across these five writers shows that "New Yorker prose" is not one style. It's a family of styles, each with measurable patterns. What unites them is craft, not sameness.

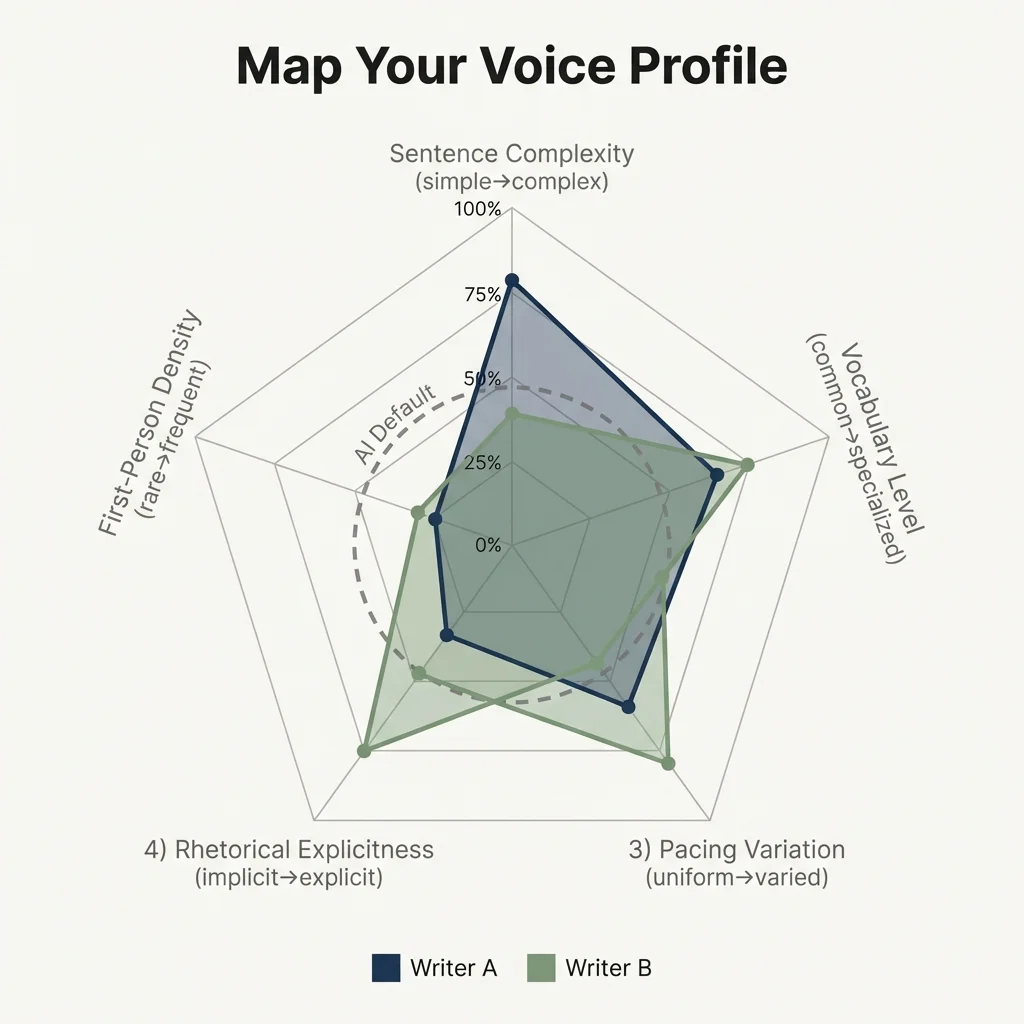

How to Analyze Our Own Writing

The same traits that set apart pro writers can map our own voice. Here's a hands-on approach.

Gather Our Best Samples

Collect 5-10 pieces we're truly proud of. Not client work we phoned in. Writing that feels fully like us. Same genre or format. Recent work, ideally from the last two years. Our voice shifts over time. We want current patterns, not college-us or first-job-us.

Systematic Analysis

For each area, check 2-3 samples and look for patterns:

Sentence Structure: Copy a 500-word section into Claude. Ask: "Give me average sentence length, range, share of simple vs. complex sentences, and any fragment use."

Word Patterns: Use the same passage. Ask: "Find recurring word choices. What intensifiers, conjunctions, and transitions repeat? What's the contraction rate? Is the word level common, educated, or niche?"

Rhythm: Look at paragraph and punctuation patterns. Ask: "How many sentences per paragraph? Which punctuation shows up often? How is white space used?"

Rhetorical Moves: Compare how pieces open and close. Ask: "How do these pieces start and end? What's the typical argument flow? How are shifts handled?"

Stance: Check our bond with ideas. Ask: "How often does first-person appear? How much hedging is there? Is the tone confident or cautious?"

Look for Patterns

The goal is to find what's consistent across samples. Those are our style traits. Variation between samples may be genre-specific or just unstable. Focus on patterns that clearly set our writing apart from generic prose.

From Analysis to Specification

We've now moved from gut feel to measurable facts. Instead of "I write in a chatty style," we can say: "I use 16-20 word sentences on average, lots of contractions, em-dashes for asides rather than parentheses, and I tend to open sections with questions."

That's the gap between telling a human our style (they can fill in the gaps) and telling AI (which needs every pattern spelled out).

The next article takes this analysis and turns it into an AI-ready style spec. That's a document that converts our patterns into rules that actually make Claude or ChatGPT match our voice. Knowing our patterns is key. Teaching them to AI is the next step.

References

- Eder, M., Rybicki, J., & Kestemont, M. (2016). Stylometry with R: A package for computational text analysis. The R Journal, 8(1), 107-121. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2016-007 ↩

- Stamatatos, E. (2009). A survey of modern authorship attribution methods. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(3), 538-556. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21001 ↩

Sample Corpus: 15 writing samples from 5 New Yorker contributors (~58,500 words total). Jia Tolentino: 3 samples (~9,000 words). Rachel Aviv: 3 samples (~24,500 words). Kelefa Sanneh: 3 samples (~6,400 words). Adam Gopnik: 3 samples (~7,200 words). Doreen St. Félix: 3 samples (~11,400 words).

Method: Stylometric analysis across five dimensions. Patterns found through comparative close reading and Claude-assisted textual analysis. All samples from publicly accessible New Yorker articles, 2024-2025.

Limitations: Small sample size provides directional insights, not definitive norms. Focus on literary journalism limits generalizability to other genres.