AI writing tools have surged since 2023. Most content workers now use AI help daily. Yet one problem keeps showing up: the output doesn't sound like us. Writers spend hours on prompts. They add examples. They describe their voice in more detail. Still the prose could belong to anyone. The editing time wipes out the speed gains.

The cycle is the same every time. We prompt the AI to "write in my voice." It gives us something competent but bland. We add more examples, more detail, more context. The output gets a bit better but still doesn't land. In the end, we spend more time editing than we would have spent writing from scratch.

The gap isn't in AI power. It's in how we describe voice. When we say "chatty" or "pro," we're using vague labels. These mean different things to each reader and each AI. But our real voice has measurable traits: sentence length, lexical density, syntactic complexity, paragraph patterns. These metrics exist in everything we write. The line between good and bad AI teamwork isn't intuition. It's whether we can turn felt voice into documented specs.

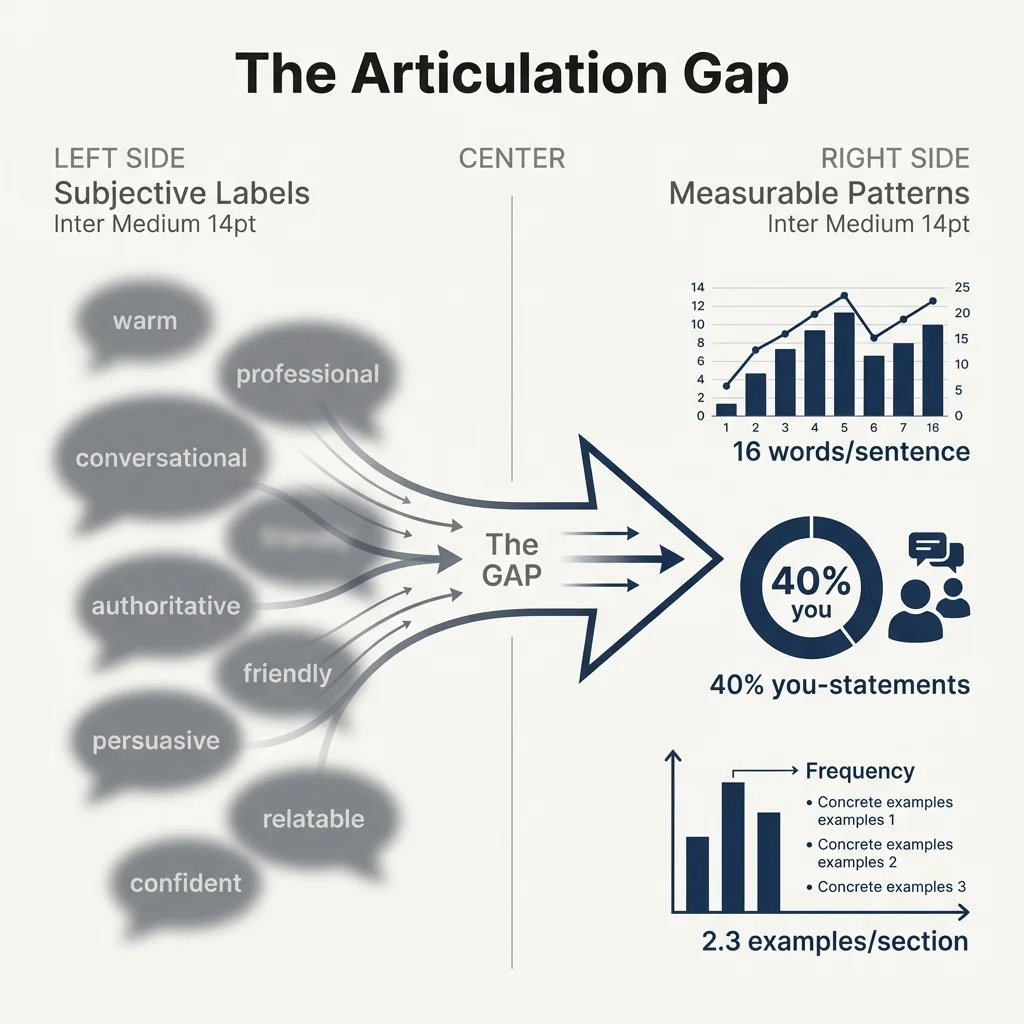

The Articulation Gap: Why Subjective Labels Don't Work

Most writers describe their voice with vague feelings. "Warm but bold." "Casual but credible." "Simple but deep." These labels feel right. We see those qualities in our own work. But they're judgments, not orders. An AI can't run "warm." It can only run patterns: sentence forms, word rates, rhetorical moves.

When writers use subjective prompts, AI defaults to patterns from its training data:

- "Professional" becomes corporate jargon

- "Conversational" becomes overly casual or fragmented

- "Authoritative" becomes unnecessarily formal

The result: generic output that sounds like no one in particular.

Compare this to asking "write like Malcolm Gladwell." The AI has hundreds of thousands of his words to study. It sees moderate sentence length near 20 words, frequent story openings, and set transitions ("But here's the thing.." "The answer, it turns out.."). These are runnable specs, not vague labels.

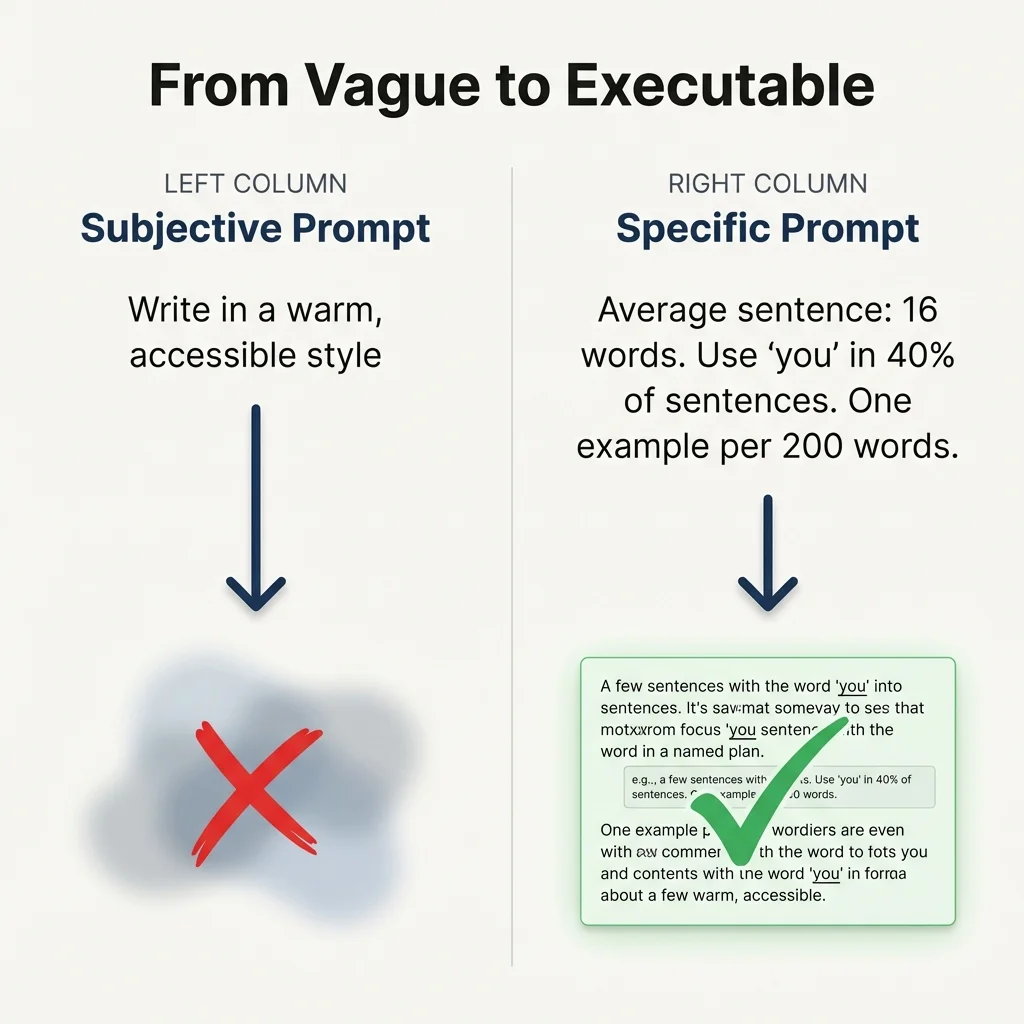

Subjective prompt: "Write in a warm, accessible style about output."

AI output: Generic, could be anyone

Specific prompt: "Write with average sentence length of 16 words, include one concrete example per 200 words, avoid jargon."

AI output: Matches measurable patterns of our actual voice

From Subjective Impression to Objective Pattern

Our writing voice isn't mysterious. It's the built-up pattern of thousands of small choices. How long our sentences run. How often we use passive voice. Whether we favor plain or fancy words. How we build paragraphs. These patterns are so steady that linguists can identify authors with over 90% accuracy using statistical analysis, a field called stylometry.[1]

The Core Measurable Attributes

Lexical patterns:

- Average word length and vocabulary sophistication

- Ratio of content words to function words (lexical density)

- Unique words per 100 words (lexical diversity)

- Preference for concrete vs. abstract nouns

Syntactic patterns:

- Average sentence length and sentence length variation

- Clause complexity (simple, compound, complex sentences)

- Use of passive vs. active voice

- Sentence openers (pronouns, conjunctions, adverbs)

Structural patterns:

- Paragraph length and variation

- Transition patterns between ideas

- Use of questions, lists, quotes

- Heading and subheading frequency

Rhetorical moves:

- How we introduce evidence (data-first vs. claim-first)

- Use of examples and anecdotes

- Second person vs. third person fix

- Hedging language vs. confident assertions

These aren't just academic numbers. They're the specs AI needs. When we say "write 18-word sentences with high lexical density," the AI has clear targets. When we say "sound smart but simple," it's guessing.

Computational stylistics shows how precise this can be. When Mosteller and Wallace studied the disputed Federalist Papers, they used common word rates ("the," "of," "to") to pin down authorship.[2] Modern AI works the same way. Published authors have large bodies of text to analyze. Our voice exists in that same measurable form. It just hasn't been documented yet.

We Already Have a Voice: We Just Haven't Measured It

We can spot our own writing at once. Drop one of our paragraphs into a lineup of similar text. We'll find it right away. That's our sentence rhythm. Our opening move. Our way of linking ideas. Our voice is steady, distinct, and already lives in all we write.

But knowing isn't the same as stating. A gut sense of our voice doesn't turn into AI orders. This is the voice gap. It's the space between "I know it when I see it" and "here's how to make it."

Think of a recipe we've cooked by feel for years. We can taste when it's right. If someone asks "how much salt?" we say "enough" or "until it tastes good." That works when we're cooking. It fails when we're teaching someone else to cook.

AI collaboration requires recipe-level precision: specific measurements, not intuitive feel.

Most writers never document their voice. They've never had to. When we're the only one writing in our voice, gut feeling is enough. AI teamwork changes that. Now we need to put the internal on paper. We need a spec for patterns we've been running on autopilot.

The good news: our voice already exists in measurable form. Every piece we've written holds the data. The task isn't to build a voice from scratch. It's to study and record the voice we already use.

The Paradox of Better AI: More Capability, Same Articulation Gap

AI writing power improves each month. GPT-4 to GPT-4o to the latest models. Each one is better at following rules, staying consistent, and matching tone. Yet the voice gap persists. Better AI doesn't solve the problem of vague specs. It just runs vague specs faster.

As AI gets better at following patterns, clear specs become more valuable. An AI that can perfectly copy any documented style is only useful if we can document ours. The bottleneck isn't AI power. It's our ability to state what we want.

This gives an edge to writers who can state their voice in measurable terms. When AI can run any given style, the writer who knows their specs can:

- Make first drafts that require minimal editing

- Maintain consistent voice across different content types

- Delegate specific writing tasks while preserving authenticity

- Collaborate with AI as a true co-writer, not just a text generator

The other path is spending more and more time editing AI output to "sound like us." That turns AI into costly autocomplete, not a real tool.

The Path Forward: From Intuitive to Documented Voice

A style spec is just what it sounds like: documented rules for our writing voice. Instead of "chatty and bold," it's:

- Average sentence length: 18 words (range 12-25)

- Paragraph length: 3-4 sentences

- Lexical density: 0.52 (moderate complexity)

- Use first-person plural ("we") throughout

- Lead with claims, support with evidence

- One concrete example per 250 words

These aren't random numbers. They're patterns pulled from our real writing. A style spec records what we already do. When we prompt AI with these specs, we're not asking it to guess what "chatty" means. We're giving it clear targets.

Before diving into full voice analysis, try this quick diagnostic to see how consistent our voice patterns actually are.

- Gather samples: Find 3-5 pieces we've written recently (blog posts, emails, reports, anything)

- Count sentences: In each piece, count the words in the first 10 sentences

- Calculate average: What's our average sentence length across all samples?

- Check consistency: Is our average within a 3-4 word range across different pieces?

If our average sentence length is consistent across different pieces (within 3-4 words), we have a measurable voice pattern. That's one specification we can give AI: "write 18-word sentences" or "write 14-word sentences."

This single metric, sentence length, is one of dozens that define our voice. But it's measurable, steady, and usable. When we prompt AI to "write sentences averaging 18 words," we get output that matches one core pattern. That's more precise than "write casually."

What's Next

The sentence length test is our starting point. In Part 2 of this series, we'll expand this approach step by step. We'll look at word patterns, structure, and rhetorical moves to build a full voice profile.

Bring writing samples. We're about to measure what we've been doing intuitively.

References

- Stamatatos, E. (2009). A survey of modern authorship attribution methods. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(3), 538-556. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21001 ↩

- Mosteller, F., & Wallace, D. L. (1963). Inference in an Authorship Problem. A Comparative Study of Discrimination Methods Applied to the Authorship of the Disputed Federalist Papers. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 58(302), 275-309. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1963.10500849 ↩