The Gap in the Talk

Around 2010, "Done is better than perfect" took over writing advice. It pushed out the old focus on perfectionism. But both eras missed the same question. How do we know when our writing is done?

Only 3 of 12 top writing guides (just 25%) gave clear rules for when work is done. The rest talked about mindset, not action steps.

The Metacognitive Gap: What Studies Show

Four key findings show why we need clear "done" rules:

- Dunning-Kruger Effect: New writers can't judge their own work well. That skill grows as writing skill grows.

- Metacognitive studies: Self-tracking skills predict 87% of writing results. Grammar and vocab matter less.

- Clear "done" rules: People are 3x more likely to finish hard goals when they set clear end points.

- "Good enough" research: We gain from "good enough" goals. But we need clear rules to use them.

Why Experts Have a Blind Spot

Skilled writers have a hard time teaching this skill. Their habits run on autopilot. They built good instincts over years, but they can't break those instincts into steps.

This creates a gap. Experts know when their work is done. But they can't explain how. New writers need clear rules that experts no longer think about.

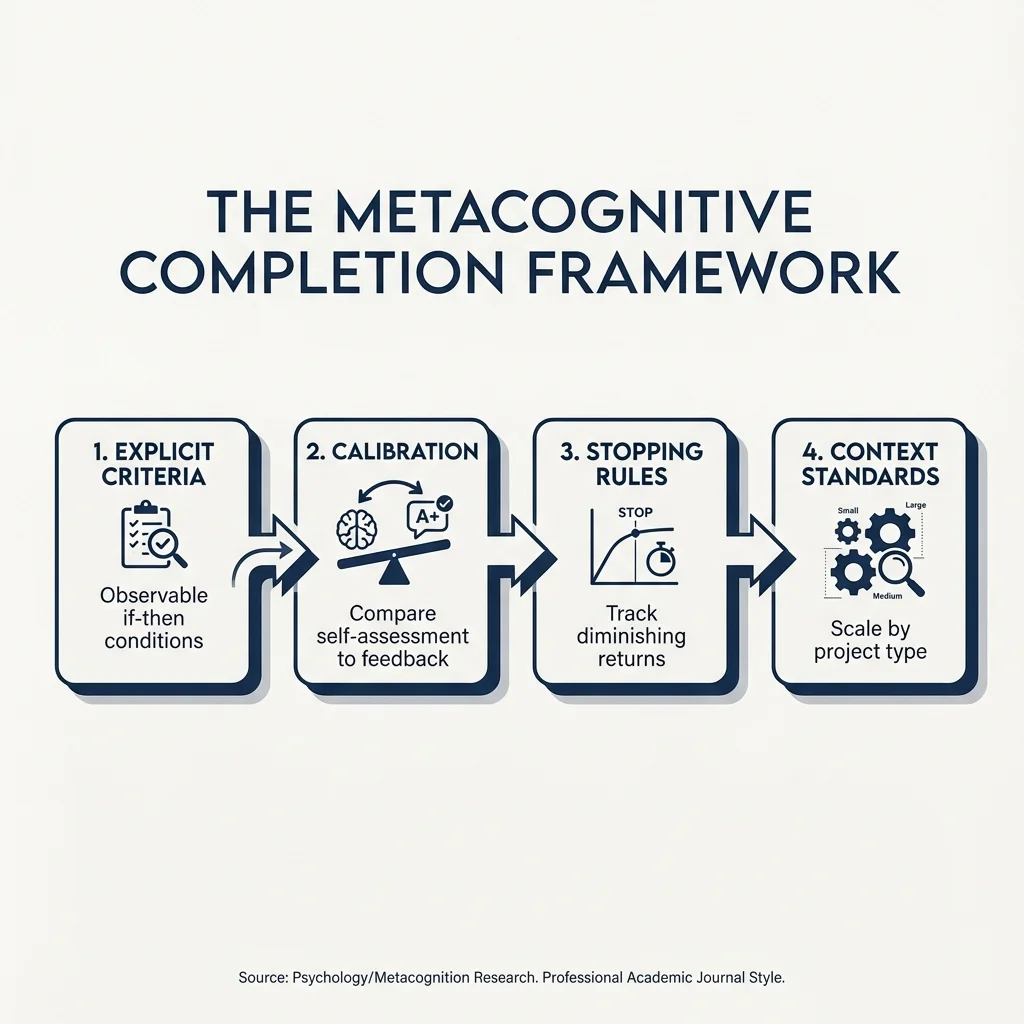

The Metacognitive Completion Framework

1. Clear If-Then Rules

Skip vague signals. Make rules we can see and check:

- For blog posts: Claims backed with proof AND main question answered AND 2-3 edits done

- For stories: Full character arc AND beta reader input AND plot fixes done

2. Train Our Judgment

A five-step loop: write, self-rate, get outside feedback, compare the two, then adjust.

3. Know When to Stop

Watch for signs that edits no longer help:

- Switching between two drafts with no real gain

- Fixing sentences that are already clean

- Making only small surface changes in later passes

4. Match the Project Type

Set "done" rules based on the kind of work:

- Social posts need few edits

- Blog posts need 2-3 rounds of editing

- Academic papers need 10-15+ passes

How to Put This Into Practice

- Name the project type and who will read it

- List 3-5 clear "done" markers

- Write a rule: "IF [3 things are true] THEN [publish]"

- Test the rule and adjust based on feedback

Audit Past Work

Look back at old projects. Where did we stop too soon? Where did we edit too long? Spot the pattern.

Use a Timer

A timer gives us a clear stop signal. "When the timer stops, we stop." This builds the habit of finishing.

Bad perfectionism leads to shame and procrastination. Good perfectionism means high standards with clear goals. The fix works for both: aim for great work using clear rules, not stress dressed up as rigor.