The Clarity Crisis in Academic Writing

Over one-fifth of abstracts now need grad-level reading skills. A study of 700,000+ abstracts from 123 journals shows a drop in clarity since 1960. Vague jargon is the main cause, not needed terms.

In 1960, 14% of papers scored below zero on the Flesch Reading Ease scale. By 2015, that rose to 22%. This trend spans 134 years.

What "Clear" Actually Means (The Metrics)

Reading Level Formulas

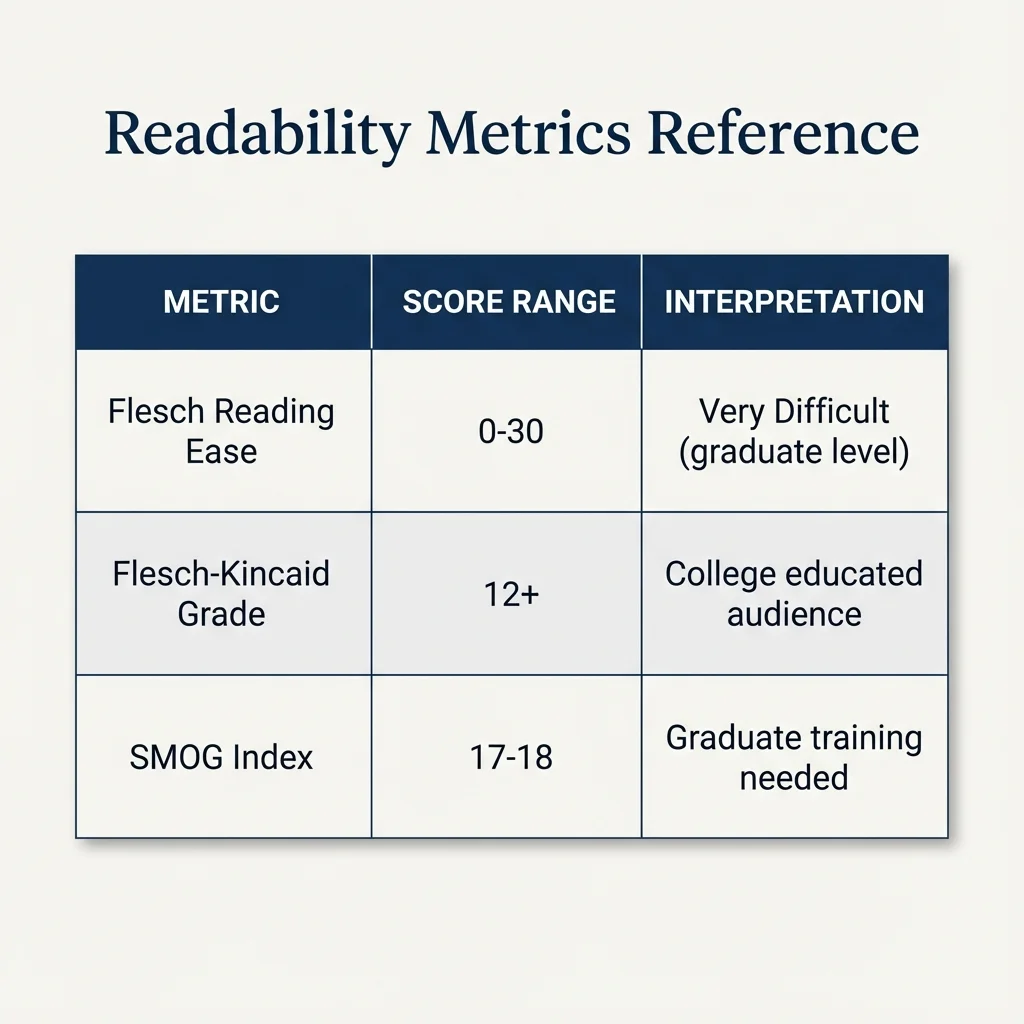

Three proven formulas measure how hard text is:

- Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level: The U.S. grade needed to read the text. Academic work scores 12-16+.

- Flesch Reading Ease: A 0-100 scale. Higher means easier. Academic work averages 20-30.

- SMOG Index: Counts long words. It predicts the schooling needed to grasp the text.

Lexical Density: Content words vs. filler words. Academic writing ranges 40-70%.

Why Academic Writing Is (Necessarily) Hard to Read

Coh-Metrix study of 200+ text traits

Harder text predicts higher quality ratings. Top-rated essays used complex traits, not simple ones.

The three top quality factors:

- Complex sentence structure

- Varied word choice

- Rare words (less common terms)

The trade-off: Complex language has real uses. It offers precision and speed for experts. Our goal is to cut waste. We keep what helps and cut what hides meaning.

Hedging: The Hidden Clarity Killer

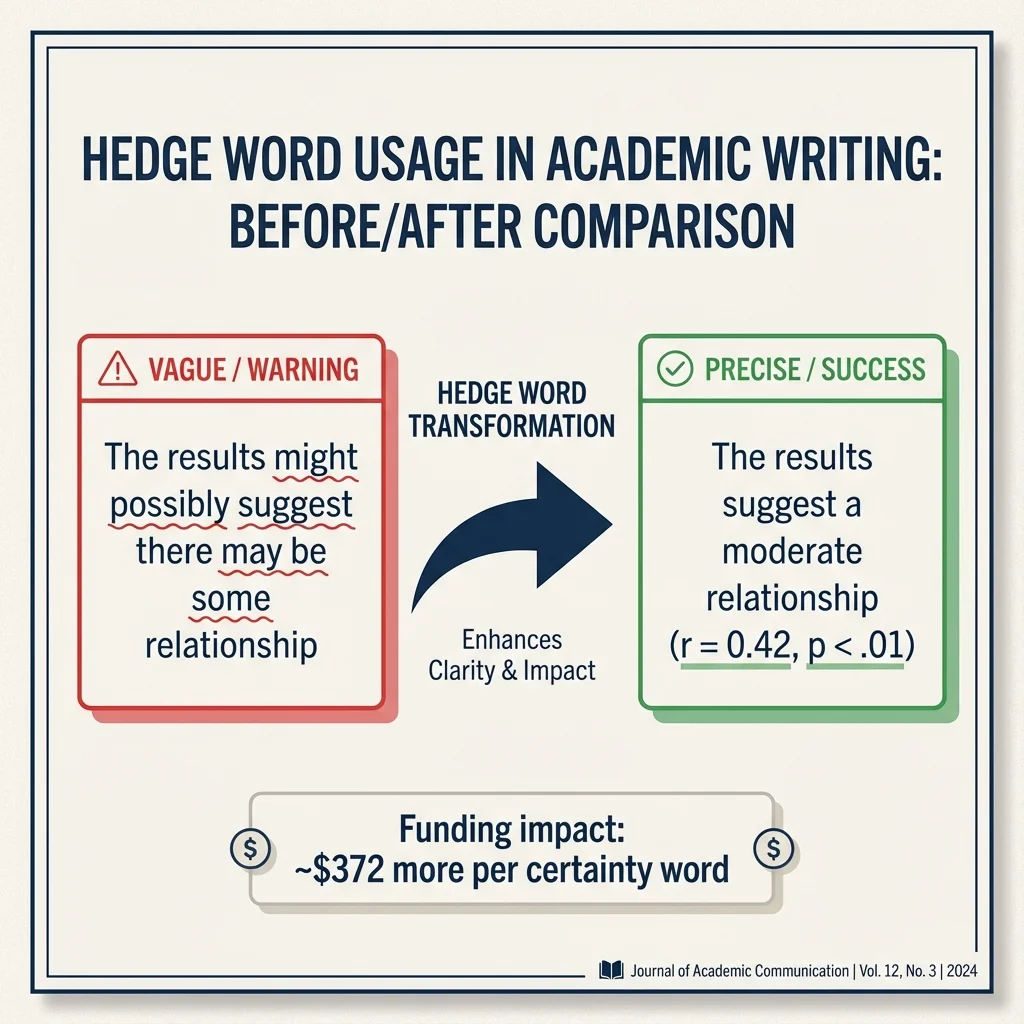

Words like "might," "possibly," and "appears" fill academic writing. Some hedging fits. Too much hides the point.

Study of 11,535 grant proposals

Grants with bold language had 53% better funding odds. NSF proposals with sure words got about $372 more per sure word.

- Use odds language, not vague words like "might"

- Hedge claims, not methods

- Lead with the strong point, then note limits

- Use no more than two hedges per section

Example Fix:

Vague: "The results might possibly suggest some link."

Clear: "The results suggest a moderate link (r = 0.42, p < .01)."

Cohesion and How Ideas Connect

Types of Cohesion

- Word-level: Repeat key terms or use close synonyms

- Reference: Use pronouns like "this" or "these"

- Linking: Use clear transitions to show how ideas relate

Key point: Cohesion's effect depends on the reader. For new readers, high cohesion helps a lot. For experts, it can slow them down.

The Old-New Rule

Start each sentence with known facts. End with new facts.

Breaks the rule: "Working memory overload results from building hard sentences while forming ideas."

Follows the rule: "Writers build hard sentences while forming ideas. This dual load fills working memory."

Practical Interventions for Measurable Improvement

- Step 1: Measure: Use free tools (Word or Hemingway Editor) to score the text

- Step 2: Fix the worst parts: Long sentences, noun chains, and hedge clusters

- Step 3: Do one pass per issue: First length, then noun chains, then hedges, then flow

Before and After

Before (51 words, Grade 22.1):

"The use of the program led to gains in the writing of those who took part, gains that might be due to the methods taught, though other factors could have played a role."

After (22 words, Grade 11.8):

"The program improved their writing. The methods taught likely drove the gains, though other factors may have helped."

Match Style to Readers

- Grant proposals: Write for non-experts. Link ideas. Cut jargon.

- Journal papers: Match the journal's reading level

- Public-facing work: Aim for Flesch-Kincaid Grade 8-10