What Is Cognitive Block?

Thinking about writing gets in the way of writing. We have ideas. We have drive. But the drafting stalls.

Research found three forms:[1]

- Editing too much while drafting

- Rigid rules about the process

- Too much planning up front

Only 13% of blocks are purely cognitive. But 40-50% have a cognitive part.

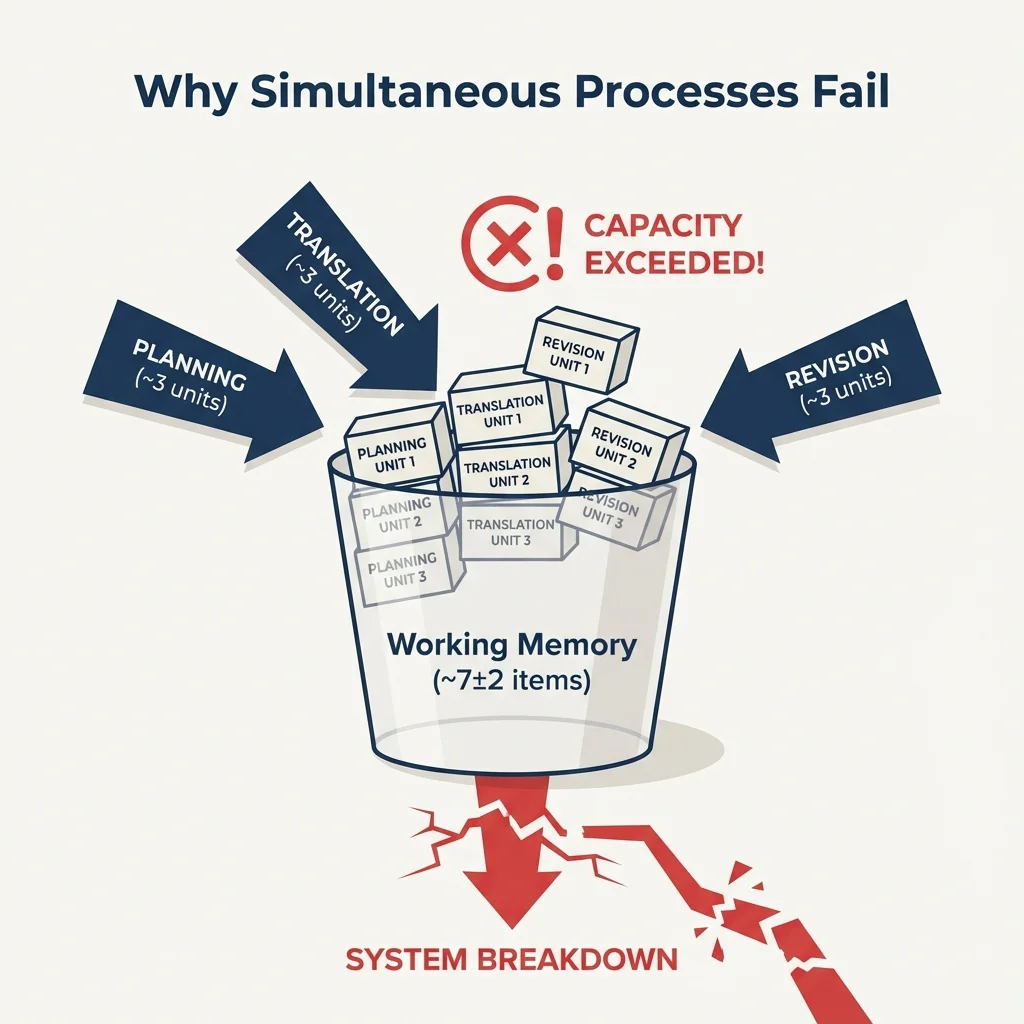

Working Memory Overload

Writing uses three tasks at once. All three draw from our executive function system:

- Planning (what to say)

- Putting words down (how to say it)

- Fixing (checking quality)

Kellogg, R. T. (1996). A Model of Working Memory in Writing

We can't max out fluency, storage, and quality all at once.

Working memory holds about 7 items. Planning takes 3 slots. Writing takes 3. Fixing takes 3. With perfectionism on, the total is too high. The system breaks.

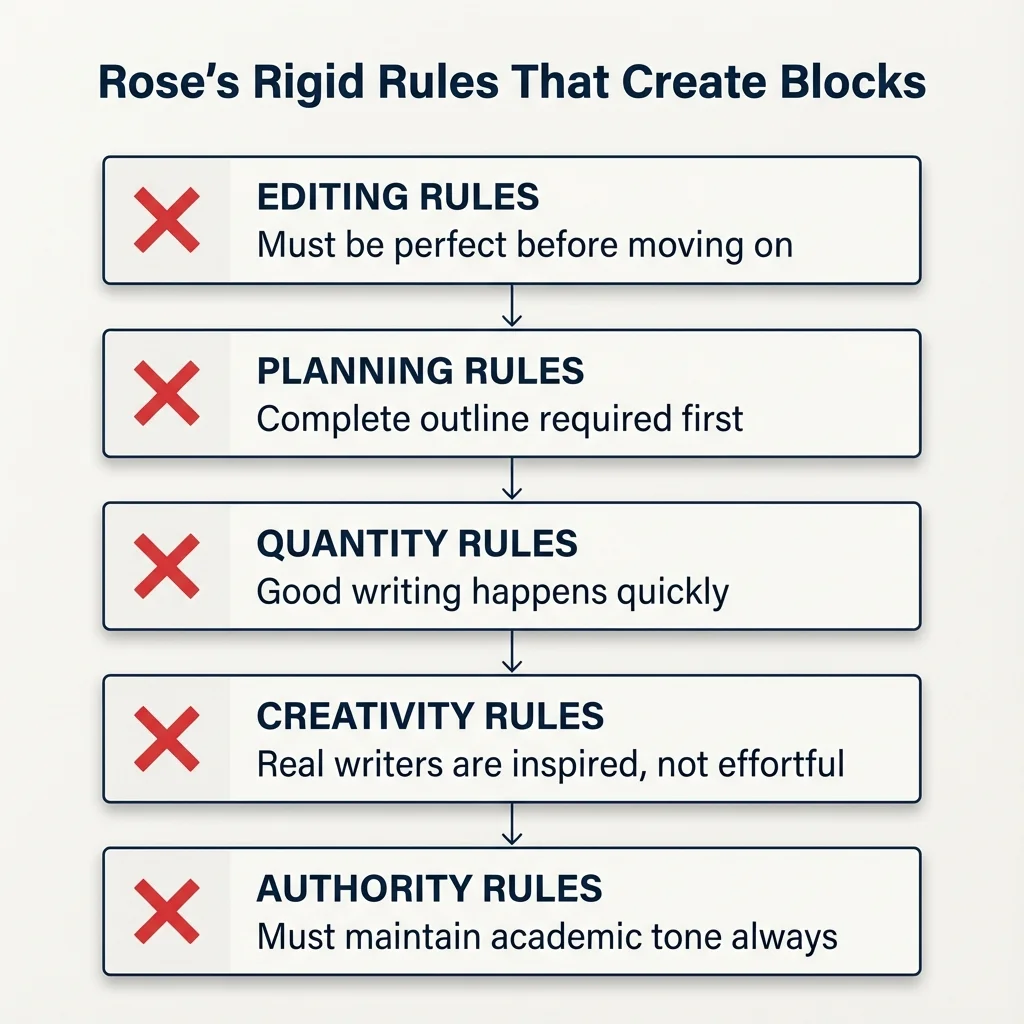

Five Rigid Rules That Block Us

These five types of rules cause blocks:

1. Editing Rules (Most Common)

- "Sentences must be perfect before moving forward"

- "First drafts should be polished"

- "Real writers don't need revision"

2. Planning Rules

- "Complete outlining required before writing"

- "Must know the ending before starting"

3. Quantity Rules

- "Good writing happens quickly"

- "Slow writing indicates lack of talent"

4. Talent Rules

- "Real writers feel inspired, not stuck"

- "Hard writing means I lack talent"

5. Tone Rules

- "I must always sound formal"

- "Simple words mean simple thinking"

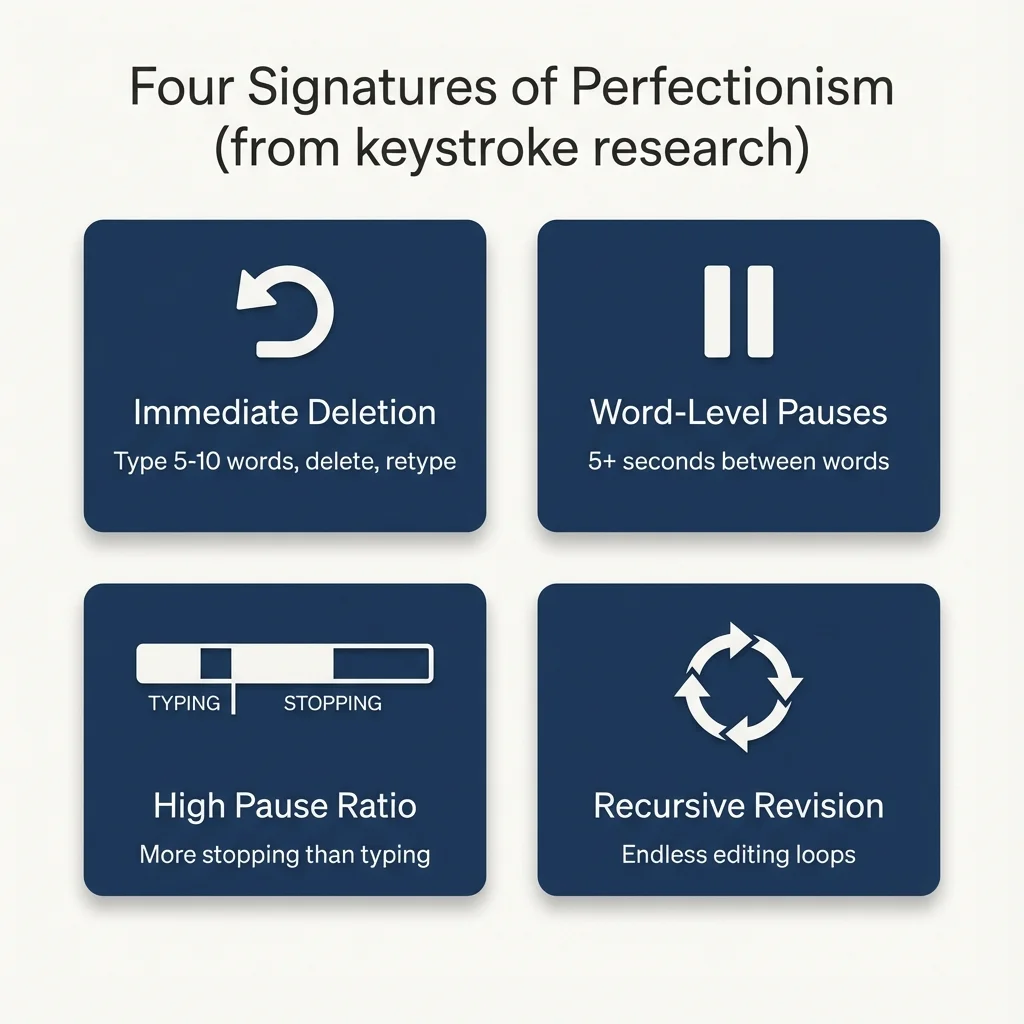

Four Signs of Cognitive Block

Keystroke research shows four clear signs:

- Quick Delete: Type a few words, erase them, retype

- Long Pauses: 5+ seconds between words

- More Pausing Than Typing: Time stalls on each line

- Going Back: Scroll up and rewrite done work

What Works

Need help right now? Our guide to fast fixes for perfectionism blocks has the quickest steps. Below is the full list.

Tier 1: Strong Evidence

- Set a 25-45 minute timer

- Write nonstop. No edits.

- Do not reread while drafting

- Edit later. Best: a new day.

- Set a 25-minute timer

- No edits until the timer ends

- Take 5-minute breaks between rounds

- The clock beats perfectionism

- Make an outline before drafting

- List key points and proof

- Follow the outline while drafting

- This frees up working memory

Tier 2: Some Proof

- Test Our Rules: Ask where they came from. Find proof they are wrong.

- Freewrite: Write 10-15 minutes daily. Never reread it.

- Bad First Drafts: We can fix bad prose. We can't fix a blank page.

What Does Not Work

- A walk (helps the body, not the mind)

- Prompts (helps planning, not writing)

- New setting (a behavioral fix, not cognitive)

- "Push through" (makes the overload worse)

References

- Rose, M. (1984). Writer's block: The cognitive dimension. Southern Illinois University Press. ↩