What Is Physiological Block?

Stress, lack of sleep, or illness drains our brain power. We can't write. But it goes beyond writing. Email, choices, and problem-solving all get hard.

Key sign: All tasks feel tough, not just writing.

Why: Stress hormones hurt the prefrontal cortex. Sleep loss cuts executive function. Illness sends our energy to healing.

Why Stress Kills Writing

What Cortisol Does

- Hurts executive function, working memory, and abstract thought

- Easy tasks still work (like making coffee)

- A bit of stress helps. Lasting stress hurts.

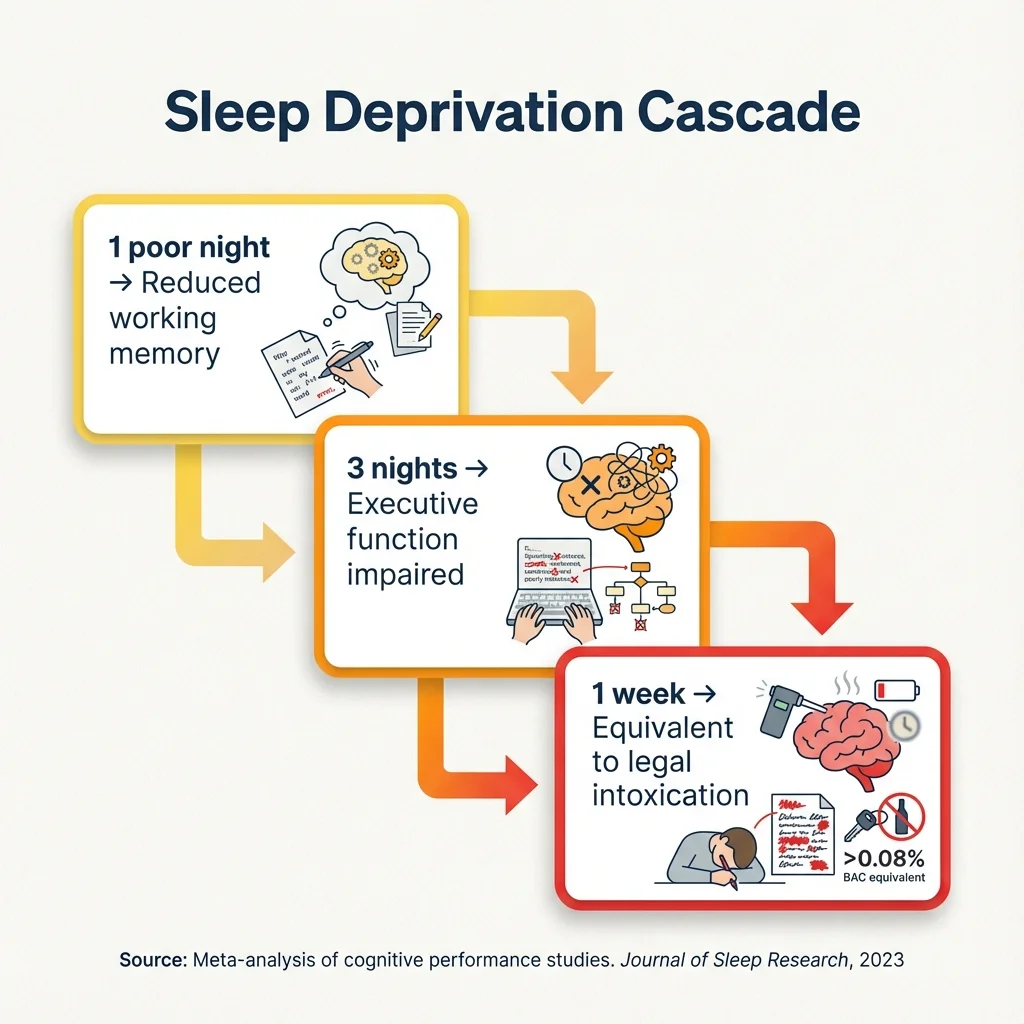

Lost Sleep Adds Up

- One bad night: Working memory drops

- Three nights: Executive function fails

- One week: Think as poorly as if drunk

Writing needs a lot from working memory. When brain power drops, hard tasks fail first. Simple tasks still work.

Stop or Keep Going?

Stop Writing When:

- All hard tasks feel broken

- Less than 6 hours of sleep for 3+ nights

- Stress that lasts more than 2 weeks

- We are sick or healing

Keep Going (With Changes) When:

- Only writing feels hard

- Just one bad night of sleep

- Short-term deadline stress

- Other hard tasks still work

What Works

Tier 1: Strong Proof (Fix the Root Cause)

- Get 7-9 hours a night for 3+ nights in a row

- Big effect on executive function (d = 0.7-0.9)

- REM and deep sleep both matter for healing

- Move: 30 minutes of cardio, 3-5 times a week

- Sit Still: 10-15 minutes of rest per day helps in 2-4 weeks

- Talk to People: Social ties ease stress

- Effect on cortisol: d = 0.5-0.8

See a Doctor: If the block lasts more than 3 weeks, get help. Rule out mood, thyroid, or sleep issues.

Tier 2: Some Proof (Ease the Load)

- Do simpler work (edit, not draft; short lines)

- Write in short bursts (15-20 minutes)

- Find a quiet space. One task. Low stakes.

What Does Not Work

- "Push through": Grit can't beat the body

- More coffee: Hides fatigue. Keeps sleep debt.

- Guilt: Raises cortisol. Makes it worse.

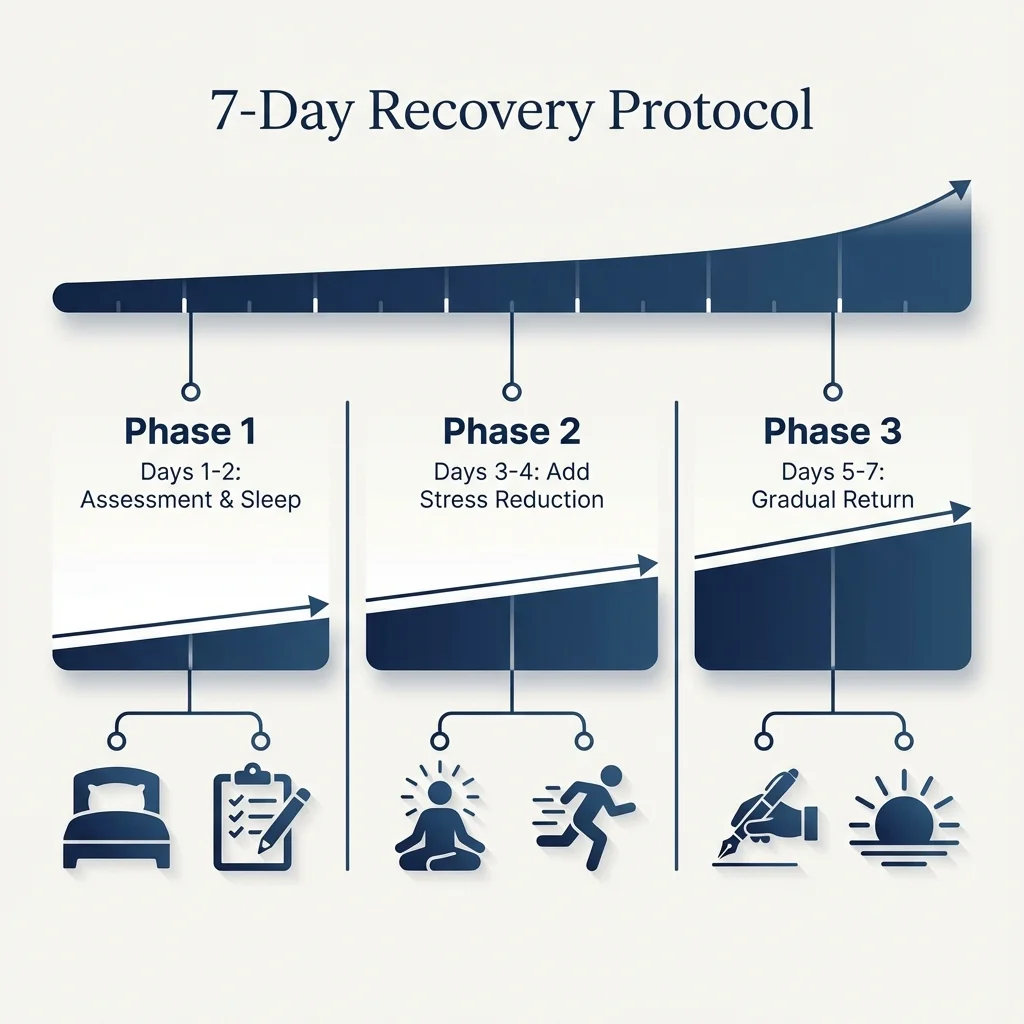

7-Day Recovery Protocol

Days 1-2: Check In and Sleep

- Start sleeping more

- Write less or take a full break

- Note how bad it feels

Days 3-4: Add Stress Relief

- Keep tracking sleep

- Add a walk or calm sitting time

- Light editing only, if at all

Days 5-7: Ease Back In

- Check in: Is our head clearer? More energy?

- Try small, low-stakes writing tasks

- Keep up the rest and relief work

This is a body problem, not a will problem. We need rest, not grit. About 7 days brings big gains. Resting now stops long-term brain harm from high cortisol.